Lightheart Adventure’s Tabletop Worldbuilding Tips

Making a world of your own takes quite a bit of preparation and forethought. Will you need to build up a continent miles away if the action takes place in one city? What’s the terrain like outside the city walls? Who owns and operates the magic shop in town? It’s also possible that you may write a novel about a neighboring town, but then the adventurers never once go there! I touched on worldbuilding briefly in an older post on my blog, but I feel it’s time to dive into some tabletop worldbuilding tips.

Geography

If you’re making your own world, you already have an idea of the kind of story you want to tell. Even a simple thesis sentence of “Evil Monarch plots to kill fated ones threatening their rule” tells us plenty about the world. We’ve got a monarch? Okay, there’s a decent-sized kingdom involved, maybe two. Fated ones from humble beginnings? At least two to three smaller towns should suffice, depending on the players’ backgrounds.

Having a plot thesis ready helps inform the kinds of landscape the story takes place in. If the main continent is suffering from a years-long drought, you may want to avoid adding water features. Conversely, make it so those lakes are either protected or hard to reach for more drama. An entire story arc could revolve around accessing that hard-to-reach water!

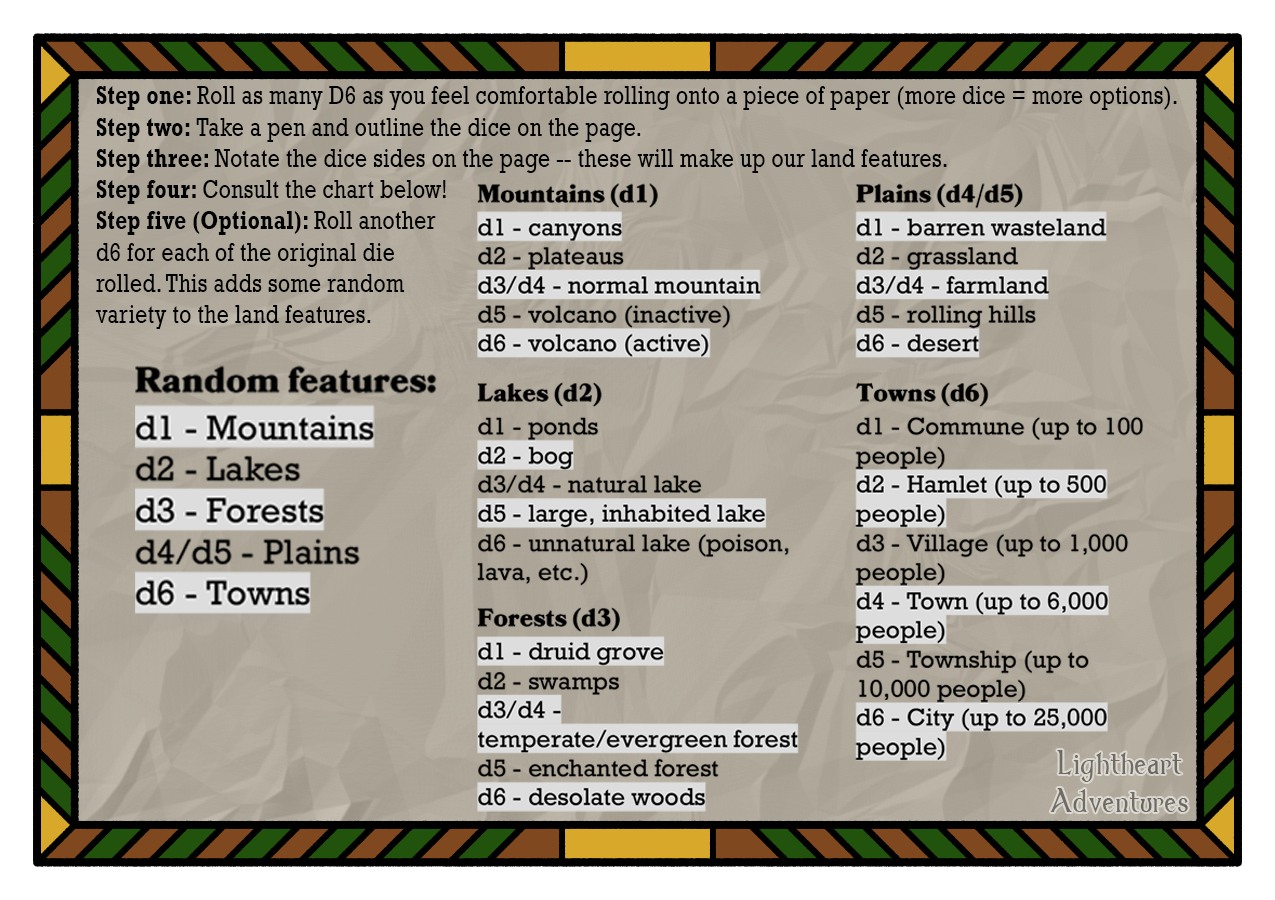

If the thought of fastidiously placing trees and mountains on a map fills you with dread, I have a handy-dandy randomized dice method that can quickly provide a basis for geography:

From here we’ve got a pretty nice beginning island/kingdom/continent and we can tweak it further if necessary. If a particular roll doesn’t make sense with the surroundings (like 5 towns clustered around an active volcano), feel free to change the die by hand or reroll it.

History

If you’re going the distance to make up a new world, you need to give it a bit of history. The trick is, unless your players actively search it out, 90% of what you write might never be seen. I can speak from experience when I say that I’ve over-written plots and had to throw most of it out when the players make choices that I could not have predicted! The ultimate goal is to recognize what content directly impacts your players and your plot and keep the details vague. This way you can change elements later to suit the adventure.

For example, a revolution took place that allowed an evil monarch to take control. It could be common knowledge who took part in the coup, perhaps from two different factions. However, you should only write about a handful of inciting individuals--even fewer if the event happened long ago and not many people from that time still live! These characters don’t need full-on character sheets worth full of backstory: only a few necessary details. Maybe a player decides that their character belongs to the nobility -- one that ties in with the warring factions. It’s easier to alter an ambiguous plot thread later if you haven’t written a 2-page backstory before. Try not to bog yourself down with convoluted specifics, and you’ll save yourself time for more player-driven developments.

The Starting Area

Unlike your world history, the adventurers are going to be spending more time exploring their immediate surroundings, so it’s integral to have a good amount of the starting area fleshed out. I’ve always GM’d under the impression that you should always know what’s over the next horizon, whether it’s a mysterious forest or a halfling hamlet.

Let’s start with a village of about 500 people. Flesh out places the adventurers are going to want to visit, such as the tavern, the blacksmith, and magic shop. Give the NPCs running these places one or two flaws, dreams, goals, or secrets. This adds more depth to these characters that the players can investigate if they want without you making a huge background for each. Maybe the Half-orc bartender has a bounty on his head from a botched kidnapping from years before, or the captain of the guard leaves town once a fortnight to spend an evening in a dark glade deep in the woods. Little touches like this might never be seen, but if the players discover one, it’ll feel like you’ve done ten times the work.

Another tip is to create a “roster” of random NPCs that you can insert into random spots as needed. Rather than dedicate time coming up with 20 different characters that fit into specific locations, spend an afternoon writing 10-15 short “character blurbs”. I occasionally use this NPC generator to help form ideas for random NPCs if I’m pressed for time. This alleviates some stress of creating characters on the fly if the adventurers explore an area you hadn’t prepared yet.

Back to the town! We’ve got people and a few buildings, but what’s outside the walls? Much like the NPC roster, I like to think up 2-3 possible encounters that the adventurers might find if they wander around the landscape. It’s possible that forest denizens harass a farmstead to the southeast, requiring the intervention of adventurers. Or the town’s herbalist needs a specific mushroom that grows deep within the bog. Whatever the case may be, having a few not-quite-developed story ideas in your playbook will help in case the players want to explore.

Horizons Beyond

I mentioned earlier that I prefer to plan “over the horizon”, but what happens if your players decide to go beyond anything you’ve written? Like the NPC roster, I suggest having a few “Side quests” that act as filler when players zig instead of zag. The ultimate goal of these side quests is to fill out a game session, thereby allowing you to continue plotting the next story beats without interrupting game flow. These mini-encounters should have some small impact on the world in general, like a wandering merchant that needs travel bodyguards. I recommend keeping the encounters to less than a page worth of detail to keep your workload low.

If you happen to be at a total loss for what to do, take a 10 to 15-minute break. This time-out helps to gather your thoughts and prepare without needing to do so in front of the players. Alternatively, if the players really go off the rails, you may have to end the session early if you don’t feel confident in improvising on the fly. Believe me, it stings to do this, but sometimes it's better to end a game early and prepare than to fumble through an unplanned encounter.

Adapting Sources

If you’re like me, you may start with the intention of writing a huge open-world backstory, but playing weekly (or even monthly) takes up too much of your schedule. I eventually adapted my D&D campaign to take place within the Forgotten Realms, which granted a wealth of pre-written world info. Suddenly my 4+ hour prep time cut down drastically as I could cherry-pick NPCs or events and insert them into the plot. There’s no shame in taking ideas to adapt for your home campaigns, especially if you’re more familiar with the content.

Pre-established lore also helps flesh out encounters and story beats, especially if your campaign takes place concurrently with notable events. Having an important NPC drop in during a session can be a huge surprise for players as well. Done right, integrating pre-written material can make a homebrew campaign truly memorable.

Wrap Up

That does it for my whirlwind approach to tabletop worldbuilding tips! Just remember to be flexible with your writing, since one crazy party of adventurers can take you places you never thought to explore.